PittsburghGetting Closer to Andy: Tracing identity in three early drawings

In my time at The Andy Warhol Museum as the Friends of the Frick Fine Arts curatorial fellow, I have become increasingly sensitive to not only the broad scope and shifting contexts of Andy Warhol’s staggering contribution to contemporary art and culture, but also to the myriad of interpretations his work has elicited. I spent the majority of my first couple of months at the museum focusing my research on issues of sexuality in and around Warhol’s artistic practice. Initially, I was drawn to Warhol’s late 1960s experimental black-and-white films and spent a portion of each day in the fourth floor film & video gallery. From there, I discovered a collection of essays inspired by a conference organized at Duke University in 1993 called “Re-Reading Warhol: The Politics of Pop.” Published in 1996, Pop Out: Queer Warhol has proven to be a landmark text that effectively challenges the hetero-normative reception of Warhol’s oeuvre. My early engagement with this material has not only helped inform my writing but has also influenced my thinking about Warhol, identity politics, and art in general.

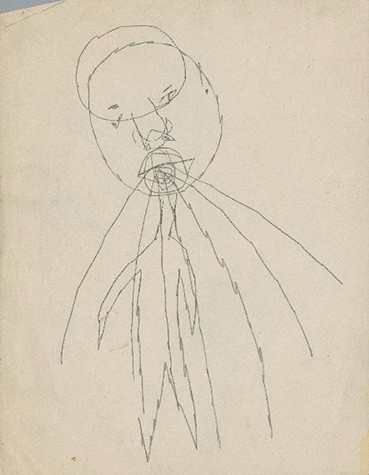

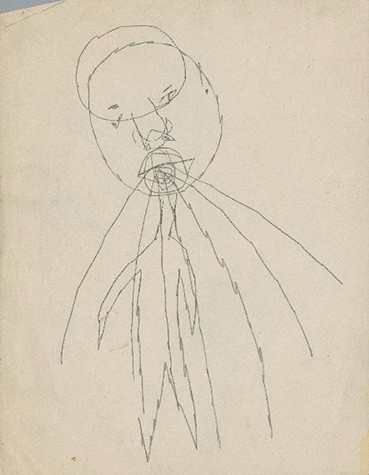

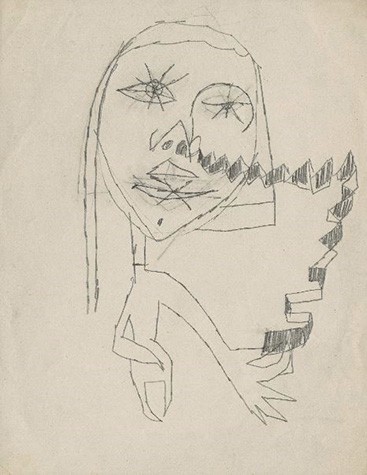

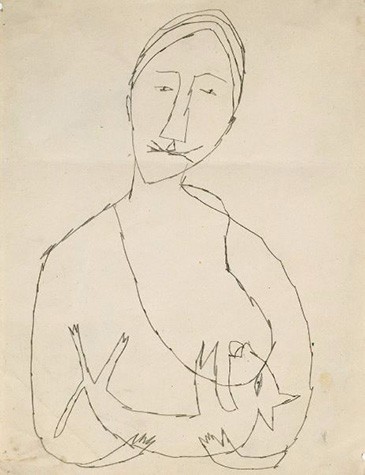

Some of my favorite works by Warhol were completed before the artist left Pittsburgh. Six scratchy pencil drawings are among the first works visitors encounter as they begin to make their way through the museum’s chronology. The exceptional images of this series compete for my attention whenever I visit the gallery dedicated to Warhol’s art school days. Three in particular, Female with ribbon extending from nose (ca. 1948), Male with lines exuding from mouth (ca. 1948), and Female with Animal at Breast (ca. 1948–49), contribute most dramatically to this curious and offbeat set of drawings. In contrast to the assembly-line effect of the mass media silkscreens for which Warhol is most famous, these impulsive and somewhat irrational works accentuate the intensity of the artist’s hand and offer an intimate glimpse into the interior world of a young Warhol.

These three early drawings share the visceral intensity of an uninhibited budding artist. In the first two compositions, both subjects seem to be willfully expelling something from their faces. The figure in Male with lines exuding from mouth is spewing an umbrella of seven thinly drawn barbed vectors from a chaotically rendered mouth. A forceful charge of rigid lines emerges from a set of agitated concentric swirls to express a sense of urgency in their expulsion down and diagonally across the picture plane. From my first experience of the piece, I could feel the anxious energy of the artist’s hand. As I revisited the drawing, I began to sense that the purging figure echoes the cathartic process of drawing itself.

Female with ribbon extending from nose performs similarly, but its effect is less fervent, and in contrast, exhibits a more whimsical scene. The eyes, nose, and mouth of Warhol’s Female are depicted frantically like the facial features he scribbled for Male with lines, but its execution is more prudently planned, achieving a more tantalizing composition. Warhol’s vigilance is evident in the erased pencil marks that are visible underneath details of the hair, eyes, and mouth. This glimpse into Warhol’s process is most alluring to me. The artist’s resolution to portray the lips as tightly pursed, instead of open with an elated grin consistent with the still legible marks underneath, allows for an enhanced interpretation of the ribbon spiraling from the nose. By sketching a hard x over the shard-chiseled lips, Warhol locates the nose as the only point of access for the figure to dispel its tangled interior. Appreciated next to Male with lines exuding from mouth, this equally enchanting piece also celebrates the relationship between its distressed subject and a therapeutic drawing practice.

Female with Animal at Breast is a more organized composition and exhibits a less erratic style of drawing, but its striking imagery stirs up a messier set of implications. The source of the work’s peculiarity is embedded in relations of gender and labor. The specification of male or female is not only signified by the inclusion of static physical traits, but is also revealed by the action of the scene. Unlike Male with lines and Female with ribbon, in which hair length is the primary attribute of gender, the hair in Female with Animal at Breast is cleverly hidden under a sequence of ribbed lines, shifting the indication of gender to the outline of the solitary left breast. By linking the primary location of gender to the bizarre action of the scene, in which the female figure is breast-feeding an infant sized dog or cat-like animal, Warhol confounds the feminine trope of mother with child. The salient eccentricities of all three drawings work together to configure a mystical corporeality that is anchored within a world situated outside of mainstream hetero-normative experience.

Warhol explicitly negotiates transferable identities through these early expressive drawings, linking them to a body of critical study based in queer identity politics. Simon Watney adds to this thinking in the essay he contributed to Pop Out: Queer Warhol (1996), in which he connects the strategies developed by a young Warhol for surviving a queer childhood to the artist’s aesthetic practice as an adult. The scholar notes, “Not for nothing did Warhol joke as a child that he came from another planet… Such fantasies speak almost too accurately (and painfully) of the experience of queer childhood, before the acquisition of an affirming identity grounded in homosexual desire” (24). Queer identities need not be understood only in terms of sexual preference, but are also concerned with navigating oppressive social realities and the unequal relations of power maintained by the hegemonic control of cultural recourses. By placing Warhol’s student drawings in this critical context, I am arguing that the above works represent an instance in which Warhol’s highly emotive and subversive themes rise to, and are in communion with, the surface of his work.

This is not to say Warhol did not regularly grapple with potent material throughout his career, as he clearly did in his Death in America and Sex Parts series, as well as in the Marilyn and Jackie portraits, just to name a few, but the early student drawings discussed here approach such threatening imagery in a far less detached manner. Warhol announces at the onset of POPism: The Warhol Sixties, “Pop Art took the inside and put it outside, took the outside and put it inside” (3). Jonathan Flatley reflects on these words in his contribution to Pop Out, and argues that Warhol opened an “outside” world to appropriation and transformation by taking public images as his palate, which in turn, enabled him to be an active participant in the public image space. According to Flatley, this reuse of recognizable images became a reliable survival tactic for Warhol and created space for him as an art world insider (102). But before it was necessary for Warhol to play the game of Pop appropriation to safely explore his place in the world, he created a series of candid drawings as a college student that appear on the paper with a lucidity that registers just as vibrantly as Warhol’s better known Pop treasures. The distance provided by the silkscreen and the mass media image is collapsed, and we are left with a body of work suffuse with the hand of the artist and yet still evocative of the powerful and often subversive imagery that Warhol regularly implemented throughout his career.

Works Cited

Doyle, Jennifer. Pop Out: Queer Warhol. Durham: Duke University Press, 1996.

Warhol, Andy, and Pat Hackett. POPism: The Warhol Sixties. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1980.