In MemoriamA Modest Memoir of a Cultural Giant, David Bowie

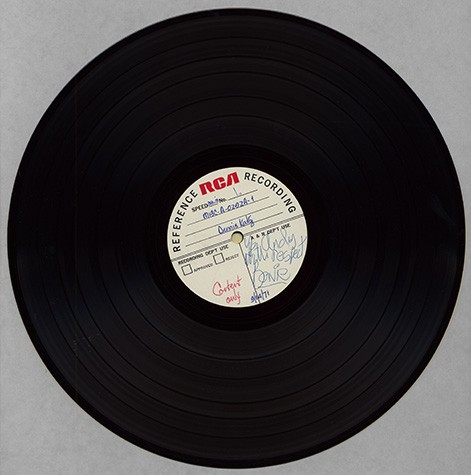

Hunky Dory / Andy Warhol, 1971, pre-release 33 1/3 rpm record signed: "To Andy with respect - Bowie" The Andy Warhol Museum; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

David Bowie was a huge fan of Andy Warhol. About 20 years different in age, both men often transformed their physical appearance (Bowie more radically so than Warhol) and were active in multiple creative disciplines, refusing to have just one identity. More important, through their profound successes, they encouraged those of us who live in the world differently (creatively or romantically), to strive for and achieve a bolder, more satisfying life. Need examples? Bjork, and Lady Gaga. If you need more: virtually every art student of the period, myself included.

In 1971, Warhol’s play Pork (based on tape recordings made in Warhol’s studio a few years earlier) was performed in London and New York. Bowie attended the London shows, having already written his songs “Andy Warhol” (!) and “Queen Bitch,” a reference to The Velvet Underground. Bowie later produced brilliant solo recordings by Lou Reed, the front man for The Velvets.

Bowie apparently didn’t meet Warhol in London. However, Tony Zanetta, Cherry Vanilla, Wayne County, and Leee Black Childers—all of whom were in the Pork cast or crew—soon became the core of Bowie’s production company in New York, MainMan. Later in 1971—through his agent at RCA, Martin Last—Bowie sent Warhol an advance reference recording copy of the Hunky Dory album vinyl pressing (as well as the “Andy Warhol” single), with song titles Bowie wrote by hand.

When David Met Andy

In September that year, Bowie visited Warhol’s Factory for the first and only time, and performed a strange mime routine; then-Factory staff member Glenn O’Brien (beginning his long career in journalism, working on Warhol’s Interview magazine) recalls that Bowie also performed his “Andy Warhol” song, although that is missing from the video recording of the event, which is in the museum’s collection. Glenn reports that the song’s lyric that Warhol “looks a scream” upset Warhol, as he was extremely self-conscious about his physical appearance.

Warhol Didn’t Paint Bowie’s Portrait

Some of Warhol’s celebrity portraits were created for the packaging of recorded popular music, such as Aretha Franklin, Billy Squier, and Paul Anka. There were conceptual designs, too: the bold banana AND the subtle blackness for The Velvet Underground album covers, the zipper AND cannibalistic Polaroids for The Rolling Stones, a punked-out passport AND 35 mm grid for John Cale, etc.

He painted conventional portraits of songstresses Grace Jones, Debbie Harry, and Dolly Parton that were not LP covers, but he never made either a conventional portrait of Bowie, nor designed any of his LP covers, for reasons unknown. Warhol also did a posthumous portrait of punk rocker Sid Vicious, for the cover of FILE magazine.

Warhol & Bowie during My Art School Days

In Nicolas Roeg’s film The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976), Bowie plays a strange visitor to our planet, who in one scene obsessively watches a massive wall of TVs. Back then, my friends and I all remarked how Warholian that scene was, as a riff on Warhol’s recently stated love of the medium (we were college freshmen; this was long before The Andy Warhol Museum). Absent physical evidence on campus, for arts and humanities students, Warhol was still a presence at Carnegie Mellon University, his alma mater (class of 1949) and mine (class of 1981). Warhol’s work was often discussed informally, or in critiques and studios; who knew? Maybe one of us had the very same workspace as Warhol.

For Bowie: as in art schools everywhere, students and younger faculty debated their favorite Bowie persona, while exploring fashion and playing music in, or alongside, local punk and New Wave bands named Dress up as Natives, Combo Tactic, Carsickness, The Cardboards, and others. All were influenced to some degree by The Velvet Underground, Andy Warhol, and David Bowie. During this period, Bowie played Pittsburgh in 1976 and 1978.

When Bowie Played Warhol

In 1996, Bowie played Warhol in Basquiat, the first film directed by Julian Schnabel (who for the prior 15 years was well known for his paintings). That gave me, as the assistant archivist at The Warhol, an opportunity to meet Bowie.

The museum had agreed to lend one of Warhol’s wigs and a leather jacket, to be worn exclusively by Bowie in the role. When shooting commenced, they were hand-carried to the set by the museum’s then-archivist John W. Smith (now director of the Rhode Island School of Design’s Museum of Art). I remember John’s excitement (and my jealousy) when he returned: “I said to David, ‘you have no idea what this means to me.’ Bowie carefully placed the wig upon his head and said, ‘YOU have no idea what this means to ME.’” It was a rare moment in the rituals of hero worship.

Months later, my turn came: the objects were needed for a Manhattan photo shoot promoting the film in Vanity Fair. I arrived in the Chelsea studio at around 8 a.m.; a breakfast buffet covered several large tables. I ate and chatted with crew members. The stars arrived: Jeffrey Wright, Dennis Hopper, Parker Posey, Gary Oldman, Willem Dafoe, and others. Eventually, (The Thin White Duke/Aladdin Sane/Ziggy Stardust/Major Tom) DAVID BOWIE arrived.

Then I Met David Bowie

He sauntered into the huge bright room, cheerfully greeting everyone. As he came closer, I thoroughly cleaned my hands and checked (for the twelfth time?) the boxes holding our precious items.

But I could never have been prepared for his greeting: “So, you’re the Warhol bloke?” said the thin man with famously mismatched eyes, (which I could not stop staring at!). “What will your next job be? Are you waiting for Jasper Johns to die?” That cracked up everyone within earshot. The brilliant, dark wisecrack demonstrated his knowledge of art history, particularly of an artist who was of great importance for Warhol (and, I’m delighted that he’s yet among us).

Bowie walked to his makeup room; I followed, carrying my treasures, hoping that he and the film crew would follow our written instructions on properly caring for the wig and jacket. I mentioned something about that and got an assurance in reply. Perhaps 20 minutes later, a commotion arose in that corner, with Bowie rushing around in his boxer shorts, hotly pursued by the makeup artist flicking a wet towel at his posterior.

Posterity and Bowie

I’ve often wondered if the experience of borrowing archival objects from a museum led Bowie to organize his own archives, which were used for the touring exhibition David Bowie Is, organized by the Victoria & Albert Museum a few years ago and still traveling (in Groningen, The Netherlands), as I write.

When the Warhol objects were returned to our museum, staff discovered that makeup had colored the wig slightly rouge, but it was also properly combed out. To my horror, I noticed that the lining of a jacket pockets had been ripped. I felt something inside, strange: a bit stiff, but yielding. I reached in, and carefully pulled it out. The mystery object was a very colorful printed card, with some metallic ink. A New York State Lottery card (a $5 winner, even!)—signed and dated by David Bowie, leaving his mark on this very personal artifact of his hero Warhol. A memento, at the very least, announcing, “I was here!”

Around 2006, I told this story to artist Glenn Ligon, who had been invited to curate an exhibition from the museum’s collections. He was very interested in the archives, and he insisted that we mat and frame the Bowie lottery ticket. It hung in his exhibition, to which he gave a title lifted from Warhol’s book, THE Philosophy of Andy Warhol (1975): “Give me another piece … smaller …smaller …” Glenn also chose to show the jacket and the same wig (one of several dozen nearly identical wigs in the museum’s collection), which my colleagues and I refer to now, informally, as “the Bowie wig.”

When the Basquiat film was released, the museum received a lovely color photograph of Bowie in his Warhol guise, as a gift from the film’s production company. Along with the treasures that Bowie had sent to Warhol in the early 1970s, I included the photo and wig in a small exhibition on our third floor devoted to Warhol’s relationship to rock-and-roll music, commemorating the recent opening of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

John Warhola (Andy’s middle brother) was a frequent visitor to the museum in those days; he would drop by my office to tell me a story or ask a question. As he studied the objects in the rock-and-roll display, he pointed to the photo of Bowie and stated, “I’ve never seen that picture of Andy before. Where is it from?” When I told him the truth, he laughed and admitted, “What? Oh, that’s really good, it sure fooled me!”

John asked if he could get a print, too. I hope that the producers replied kindly to his inquiry!