EssayWarhol’s Confession: Love, Faith, and AIDs

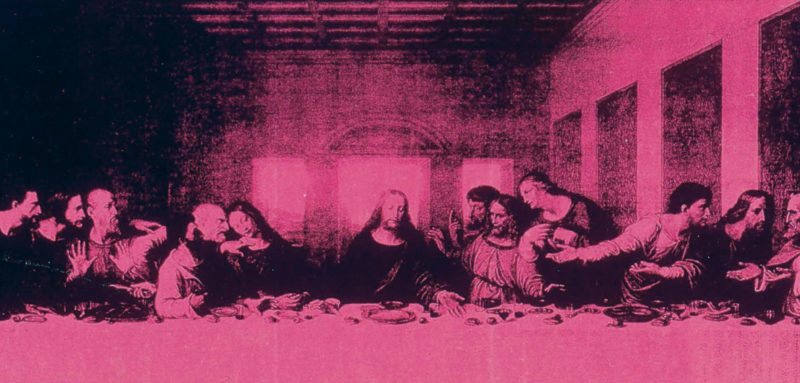

A. Andy Warhol, The Last Supper (detail), 1986

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

1998.1.355

A Note from the Author

At the time I was writing this text and doing this research, it was taboo, unheard of, to write about Warhol and AIDS. Not only had other scholars dismissed Warhol’s response to the epidemic as a failure but exploring his personal connection to the disease was deemed unproductive. Even more, so much of his late career has been written off as the worst of Warhol. This essay was an attempt to finally bring weight and grit to Warhol’s religious works and to provide a socio-political lens for understanding the connection between Warhol’s faith and sexuality as a response to the disease. Critical to this narrative was to highlight Warhol’s frank and emotional responses about AIDS and his relationship with Jon Gould, his late boyfriend who died of the disease in 1986, in his Diaries.

The concept for this essay started with an exhibition I curated in 2016 called Andy Warhol: My Perfect Body, which explored Warhol’s late physiological diagram and religious paintings. I was surprised by the abundance of works focused on health, physical strength, and perfection in 1985-86—a year that AIDS was devastating Warhol’s professional and personal circles in New York. The media at the time had framed the disease in moralistic and religious language provoking fear and paranoia by targeting communities such as homosexual men, who were deemed immoral, threatening and deserving of disease for their perceived “licentious” behavior. Learning that his late-lover Jon Gould had died of AIDS at 33 in 1986 coalesced the connection to Warhol’s religious works, which he started that year as, I argue, a response to the crisis.

Living now during a public health crisis, we can better understand and also embody the fear that Warhol and his community would have felt during the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s. This contemporary moment too helps us all see Warhol’s late career as deeply personal, emotional, and spiritual.

I’ve got these desperate feelings that nothing means anything. And then I decide that I should try to fall in love, and that’s what I’m doing now with Jon Gould, but then it’s just too hard.

I’m going to the doctor who puts crystals on you and it gives you energy. . . . Jon’s gotten interested in that kind of stuff—he says it gives you “powers,” and I think it sounds like a good thing to be doing. Health is wealth.

Warhol’s Confession: Love, Faith, and AIDs

Nearly thirty years have passed since Warhol’s retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in 1989, and the perception of his work and legacy has shifted quite dramatically. Warhol the queer artist, Warhol the filmmaker, and Warhol the photographer have all emerged in new lights.1 If Robert Rosenblum, in his catalogue essay for that first retrospective, “Warhol as Art History,” could pitch the artist as a painter situated safely within the canon, the discourse has now expanded to recognize the sexual and transgressive nature of Warhol’s practice through a discussion of queer politics and cultural studies.2 While the literature has blossomed since the 1990s, a need for revision remains: there has been a tendency to stretch Warhol to please the needs of various postmodernist camps, and repetition in the narrative has led to a scholarly imbalance, an almost fetishistic focus on Warhol’s output of the 1960s. His final paintings are neglected and rejected and a serious investigation has yet to be undertaken. In particular, the divide between the readings of the “queer Warhol” and of the “religious Warhol” has perpetuated a misunderstanding of his Last Supper paintings and his response to the aids epidemic. What would it look like if these two camps merged?

In the final decade of his life, sparked by collaborations with younger artists Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring, Warhol returned to painting by hand, on a dramatic scale, and with new energy. He also spent this period sealing his place in the canon, engaging contemporary issues of technology and politics while appropriating details from Renaissance and modern masters ranging from Botticelli and Raphael to de Chirico. No theme compares in number to the nearly one hundred works in Warhol’s Last Supper series, produced between 1985 and 1986. The dilemma in the current literature on these paintings is that it often makes little reference, and sometimes no reference at all, to the major crisis affecting Warhol’s community at the time of their completion: the AIDs crisis. The ambiguity in the writing on the last decade of Warhol’s career stems in part from the conflict between his Byzantine Catholic faith and his homosexuality. This tension is often ignored in discussions of the work, with the result that the paintings appear one dimensional. Warhol made productive use of this tension across his entire career, alternately flaunting and concealing his sexuality in his work. Once these issues are brought to the forefront, a broader concern with mourning and salvation emerges as the crux of the Last Supper paintings.

In 1984, the art dealer Alexander Iolas, an Egyptian-born former ballet dancer and an eccentric collector of Surrealist and other early modernist art, commissioned Warhol to create a series of paintings and prints based on Leonardo da Vinci’s iconic Last Supper. Warhol’s final exhibition during his lifetime, Warhol—Il Cenacolo, featured at least twenty of these works and was staged in 1987 in the refectory of Milan’s Palazzo delle Stelline, which then housed the bank Credito Valtellinese.3 The venue was selected for its proximity to Leonardo’s masterwork, which was painted in 1495–98 just across the street, in the refectory of the Dominican cloister Santa Maria delle Grazie.4 While Warhol exhibited a modest sampling of paintings and prints in Milan, he had spent a year producing nearly one hundred additional renditions of The Last Supper.5 The commission, the last of the artist’s career, became a near obsession for him. In prophetic fashion, these images of the eve of Christ’s crucifixion marked the end of Warhol’s own career and, indeed, his life. Just a month after returning to New York from the opening in Milan, he was admitted to the hospital for gallbladder surgery and died.

Warhol’s production in relation to The Last Supper is remarkable for its quantity and diversity, including works on paper, large-scale paintings, and even the sculpture Ten Punching Bags (Last Supper) (1985–86), a collaborative work created with Basquiat. Warhol employed two distinct methods and styles in these works: one in which he stayed closer to Leonardo’s original by screenprinting a photograph of an engraving of the mural on canvas, the other in which he departed from it by combining hand-painted images of Christ with commercial logos and text pulled from newspaper headlines and advertisements. Ultimately both versions present commentaries on suffering, one through repetition, the other through signs and symbols.

Few works of art are as celebrated and studied as The Last Supper, yet the original as Leonardo executed it on the refectory wall has not existed for more than five hundred years.6 Painted with an experimental technique on dry plaster, the image began to deteriorate within a few years after its completion. Shifting trends in conservation and decades of painstaking repair have only succeeded in salvaging select details. Yet time has not muted the emotional vibrancy of the disciples, or the complexity of the perspectival lines and dueling gestures among the figures’ hands and feet, which symbolically point within and beyond the pictorial field. No matter how faded by age, these elements continue to perplex and inspire art enthusiasts and scholars worldwide. Art historian Leo Steinberg contended that the strength of Leonardo’s masterwork lies in its inherent duplicity: since the nineteenth century, writers have argued over which event—the revelation of Christ’s betrayer or the celebration of the Eucharist—is more clearly indexed by the dramatic gestures among the disciples.7 Adding to the sustained interest in the work is the way it’s studied, often from copies—engravings and other reproductions—that have varied over time as the original has deteriorated. Leonardo’s Last Supper is a kind of meaning machine.8

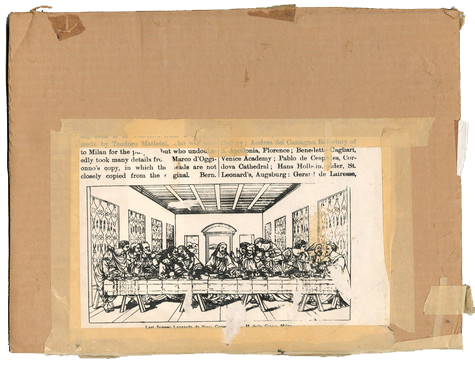

Warhol’s screenprinted canvases from 1986, such as Pink Last Supper (fig. A), Camouflage Last Supper (pages 378–80), and Sixty Last Suppers, are sophisticated paintings that oscillate between flatness and illusionistic depth, ideas that lie at the heart of Renaissance painting. His source for these canvases was a photograph of a print similar to a widely distributed engraving made in 1800 by Raphael Morghen; the hand-painted series, meanwhile, drew from an image in the Cyclopedia of Painters and Paintings (fig. B), first published in 1885.9 In the way he looked to these sources, his process was not so dissimilar from that of the scholars and enthusiasts before him: many celebrated writers of the Enlightenment, for example, such as Goethe, based their studies on Morghen’s engraving, a copy that left out the symbolic wineglass under Christ’s right hand.10 (Morghen himself created his famous engraving from a drawing by another artist, who in turn seems to have been working from a drawing by another artist still.)11 Warhol, who worked throughout his career with reproductions as source material, understood the inevitable loss or change of meaning in the facsimile. He also understood how a reproduction can exist in suspended time. By the 1980s, he had fully embraced contemporary media—television, photography, and even the Amiga computer—and had launched his own television show, Andy Warhol’s T.V., which aired from 1980 to 1982. Culture as mediated experience is the appropriate lens through which to view these paintings. In his handling of color—pink, red, yellow, and camouflage—or of repetition, as in the expansive canvas Sixty Last Suppers (fig. C), with its abutting black-and-white rectangles that look like stacks of miniature television screens, Warhol created a meditation on the shifting nature of death and suffering in the face of modern media. These were only the latest episodes in a sustained engagement with the fusion of mourning and media that he started in the early 1960s with his Death and Disaster series, which framed death through a screenprinting technique mirroring the 16mm filmstrip.

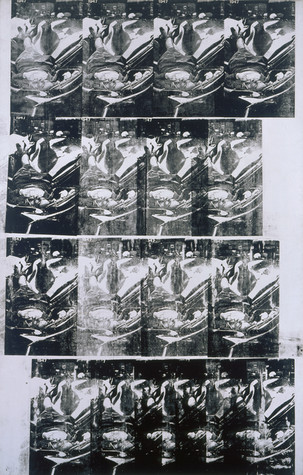

Warhol created these paintings, among his most celebrated, in early 1963 through 1964, copying scenes of suicides and car accidents from periodicals such as Newsweek and Life. For a suicide painting completed in 1963, 1947 White (fig. D), he sourced a Life photo by Robert Wiles of a young woman—Evelyn McHale, a twenty-three-year-old bookkeeper—who had leapt to her death from the eighty-sixth floor of the Empire State Building.12 The young beauty landed on the roof of a limousine, where the vehicle’s twisted metal perfectly cradled her fall, leaving her body miraculously unmarked and her posture frozen like a sleeping beauty. Warhol printed this image in an overlapping sequence that mirrors the shape and structure of the filmstrip. The repetition and movement in works like this one heighten and disrupt the trauma of the original event: the victims take on saintlike qualities as their suffering becomes beautiful.

As if revisiting this technique, Warhol printed his Last Supper paintings with a similar formal reference to the moving image, specifically the cube of a television screen. Through the shadowed abstraction in Camouflage Last Supper and the tightly framed grid in Sixty Last Suppers, repetition and printing techniques both nullify and heighten the spiritual strength of the original image. In 1947 White, Warhol had overlapped the frames of the silkscreen and created a sense of movement by printing the image from light to dark, a visual effect that mirrored the flicker and motion of a filmstrip; in Sixty Last Suppers and other works the repetition is static, locking the image in time.

The logic of this shift may reflect the moment at which these images were frozen, a moment of public suffering for the homosexual body. In the 1980s, branded in the media as the primary bearer of AIDS, the gay male body became a symbol of moral and physical decay. Because the spectacle of AIDS involved repeated images of the withered and wrinkled bodies of the ill, as Simon Watney has argued, “any possibility of positive sympathetic identification with actual people with AIDS [was] entirely expunged from the field of vision”; instead, political and public commentary on the crisis “relayed between the image of the miraculous authority of clinical medicine and the faces and bodies of individuals who clearly disclose the stigmata of their guilt.” “The principal target of this sadistically punitive gaze,” Watney continues, “was the body of the homosexual.”13

Created at the height of the AIDS crisis, Warhol’s Last Supper series generated a startling number of works showing the face of Christ and the eve of his death. Given the punitive rhetoric directed at homosexual men during this period, it is surprising that what scholarship exists on the series has been notably silent on the cultural climate of their creation. The author responsible for the most extensive writing on Warhol’s religious works is Jane Daggett Dillenberger, whose research traces a trajectory from the artist’s Byzantine Catholic upbringing in Pittsburgh to the Last Supper commission. Dillenberger, a theologian as well as an art historian, seems to have found AIDS taboo, since she makes no reference to the epidemic in her book.14 It is not only in the work of traditional art historians and scholars of religion, however, that Warhol’s response to the AIDS epidemic is misunderstood; contemporary theorists have neglected this topic as well. The first collection of critical essays on the queer politics of Warhol’s work, Pop Out: Queer Warhol (1996), maintains a near silence on Warhol’s religious life. Here, Jonathan Flatley, in an otherwise persuasive essay on the complexities of identification in Warhol’s practice, argues that Warhol failed the AIDS movement with his “depressing” depiction of the crisis in his 1985–86 canvas AIDS, Jeep, Bicycle (pages 350–51).15 But Warhol’s commingling of commercial branding and images of Christ in these works commented on the cultural climate of the time in ways that even the most thoughtful commentators have overlooked.

By the early 1980s, the AIDS epidemic was beginning to gain public recognition in major cities in the United States and abroad, mainly New York, San Francisco, and Paris. The syndrome first came to wide public notice with an article in the New York Times in 1981 under the headline “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals,” which shared reports from doctors in New York and San Francisco who were diagnosing homosexual men with a rapidly fatal form of cancer.16 Out of the forty-one patients tested, eight died less than twenty-four months after the diagnosis. Panic and anxiety spread quickly within the homosexual community and the term “gay cancer” was adopted to describe the disease. By May 1982 the Times had firmly connected the disease with homosexual communities through the headline “New Homosexual Disorder Worries Health Officials.”17 Headlines from 1981 onward became more alarming as public figures and celebrities, most famously Rock Hudson, began to die of AIDS.

The first mention of “gay cancer” in Warhol’s diaries came on February 6, 1982, not even a year after the New York Times article, in reference to Joe MacDonald, a male model whom the artist had photographed in the 1970s and who would die of AIDS in 1983. Warhol recounts,

I went to Jan Cowles’s place at 810 Fifth Avenue where she was having a birthday party for her son Charlie. . . . Joe MacDonald was there, but I didn’t want to be near him and talk to him because he just had gay cancer. I talked to his brother’s wife.18

Just a few months later he referenced the New York Times directly in a diary entry from May 11, 1982:

The New York Times had a big article about gay cancer, and how they don’t know what to do with it. That it’s epidemic proportions and they say that these kids who have sex all the time have it in their semen and they’ve already had every kind of disease there is—hepatitis one, two and three, and mononucleosis, and I’m worried that I could get it by drinking out of the same glass or just being around these kids who go to the Baths.19

In each of the eight references to “gay cancer” in The Andy Warhol Diaries, Warhol expresses fear of contracting the disease from the most casual of encounters, and the underlying tone of his remarks is loaded with judgment.20

Warhol’s anxiety about health and illness had started during his youth, with an early onset of Saint Vitus’ dance, and his fear of hospitals unquestionably mounted after his shooting in 1968. But his attention to health, alternative medicines, and physical fitness peaked in the 1980s, a period of growing public paranoia over AIDS and of the social targeting of homosexual men. His work began to reflect these worries between 1985 and 1986, in paintings such as The Last Supper (Be a Somebody with a Body) (page 344), which juxtaposes bodybuilding imagery with benevolent images of Christ—the same Christ seen in the Last Supper works. Given Warhol’s preoccupation with disease and illness, it is easy to imagine the shock he would have felt in 1984, when he found out that his then boyfriend, Jon Gould, had been admitted to the hospital with pneumonia. A little more than two years later, in September of 1986, Gould died from AIDS, at the age of thirty-three.

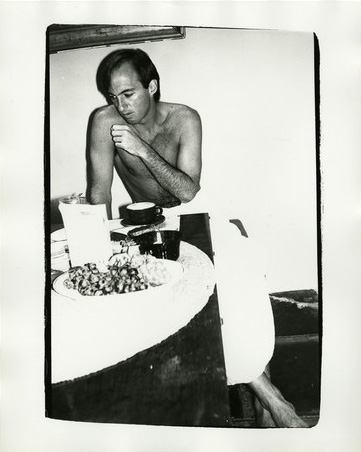

Despite an age difference of twenty-five years, Gould and Warhol were involved for five years, traveling together, working together, and, for a short period, living together (fig. E). When Gould met Warhol, he had just landed a competitive producing position with Paramount Pictures. A former student in Harvard’s Radcliffe Publishing Program and from a wealthy New England family, he had a certain pedigree that attracted the artist. As Bob Colacello would write, “Old money, Harvard, Hollywood—it was a résumé that Andy couldn’t resist. And there was something else about Jon Gould that drew Andy toward him: like Jed [Johnson], he had a twin brother named Jay.”21 Johnson was an aspiring interior designer who had worked for Warhol at the Factory and had famously decorated the artist’s town house. Before becoming involved with Gould, Warhol had dated Johnson (twenty years his junior) for twelve years. Given the time they spent together, it’s surprising to read how passive Warhol’s mentions of him are in the diaries. By stark contrast, Warhol was infatuated with Gould, and his writing on him sometimes has a tone of desperation. In an entry of June 12, 1981, just six months into their relationship, Warhol says candidly,

Jon was back in town and he said he thought I was going away so he’d made plans to go away for the weekend and so I guess my whole relationship’s fallen apart. He said he’d call me and didn’t, which was mean. I have to pull myself together and go on. I have to get a whole new philosophy. I don’t know what to do. I watched Urban Cowboy, and John Travolta just dances so beautifully. It was a really good movie. A Paramount movie, so that made me think more about Jon and I felt worse. I cried myself to sleep.22

Beyond the hundred entries in the diaries, Gould is the most photographed subject of Warhol’s late career, appearing in more than four hundred of the 3,600 contact sheets the artist produced between 1976 and 1987.23 Warhol’s interest in Gould’s muscular physique and youthful athletic acumen is apparent in hundreds of photographs of Gould shirtless, jogging, and sunbathing. Gould was a complicated figure in Warhol’s life and a source of tension within his close-knit circle of employees. Infighting was part of the culture of Warhol’s circle. Stories of disputes between Gould and the photographer Christopher Makos, the friend and matchmaker responsible for introducing Warhol to Gould, are well recorded in the diaries, and, unsurprisingly, Warhol seemed to thrive on the jealousy. What he seemed most to appreciate was Gould’s closeted sexuality, his insistence on hiding their relationship. Warhol writes in the diaries, “I love going out with Jon because it’s like being on a real date—he’s tall and strong and I feel that he can take care of me. And it’s exciting because he acts straight so I’m sure people think he is.”24 This form of secrecy fit in perfectly with Warhol’s lifelong practice of both flaunting and concealing his own sexuality. Their relationship also satisfied his concern with putting his love interests to work: the possibility of using Gould to land a movie deal at Paramount, and the blurring of work with pleasure, was part of the mystery of their love affair. As Warhol reveals in the diaries,

Oh, but from now on I can’t talk personally about Jon to the Diary because when I told him I did, he got mad and told me not to ever do it again, that if I ever put anything personal about him in the Diary he’d stop seeing me. So from now on, it’ll just be the business angle in the Diary—he’ll just be a person who works for Paramount Pictures who I’m trying to do scripts and movies with.25

Work for Warhol was the perfect shield for concealing his feelings and sexuality.26 Given the emotional tenor of Warhol’s writing on Gould in the diaries, his anxiety over the discovery that the AIDS virus had been incubating in the body of the young man whose bed he had shared seems undeniable. The details of their physical intimacy have been the subject of rumors and speculation, but it is to some degree irrelevant here, since Warhol, and much of the public at the time, believed that AIDS could be transmitted by casual contact.27 In the published edition of the diaries, the first mention of Warhol’s knowledge of Gould’s illness appears as an editor’s note inserted into the entry for February 4, 1984, the dueling voices in the passage functioning like the slippages and tears in the Death and Disasters series:

Did a personal errand with Jon, but he made me promise not to put anything personal about him in the Diary. [Jon Gould was admitted to New York Hospital with pneumonia on February 4, 1984, and released on February 22. He was readmitted the next day, however, and released again on March 7. On that day Andy instructed his housekeepers Nena and Aurora: “From now on, wash Jon’s dishes and clothes separate from mine.”]28

Warhol’s inability to speak about or record loss in the diaries is the mirror of his depiction of death in the Death and Disasters. The slip-pages and tears on these canvases from 1963 and 1964, his most celebrated depictions of death, function, Hal Foster has argued, as a form of “traumatic realism.” For Foster, the work repeats a traumatic image of the “real” in order to defend against it by draining it of significance, but the “real” nevertheless pokes through, in the form of a repeated emotional detail or technical flaw. “Repetition in Warhol,” he writes, “is not reproduction in the sense of representation (of a referent) or simulation (of a pure image, a detached signifier). Rather, repetition serves to screen the real understood as traumatic.”29 Foster compares this underlying current to Roland Barthes’s idea of the punctum, the element in a photograph that “rises from the scene, shoots out like an arrow, and pierces me.”30 This process of screening the traumatic is also at work in the diaries, which, like the Time Capsules (1974–87), present an obsessive recording of daily life and a false sense of intimacy. In the published version, the endless entries of the mundane—taxi receipts, dinner checks, party invitations, gossip—work to repress the real, while editor’s notes such as those on Gould’s illness, and later on his death, rupture the illusion to reveal a slippage of truth, piercing like the punctum to let the “real” through:

Susan Pile called and said she got a job at Twentieth Century Fox that starts in October, so she’s leaving Paramount. And the Diary can write itself on the other news from L.A., which I don’t want to talk about. [Note: Jon Gould died on September 18th at age thirty-three after “an extended illness.” He was down to seventy pounds and he was blind. He denied even to close friends that he had AIDS.]31

In entries like this one, the outside world intrudes upon the fantasy of intimacy in the diaries, and the crisis in Warhol’s personal life becomes all the more clear from what goes unsaid. Consideration of the sociopolitical climate in which Warhol was producing the Last Supper paintings, and of his private relationship with Gould, allows the link between AIDS and these works to start to emerge. In fact he began the series, which would turn out to be his last, within days of Gould’s death.32

The tension between Warhol’s sexuality and his religious life has its fullest expression in paintings such as The Last Supper (The Big C) (1986; fig. F), in which signs and symbols create a private reference to AIDS. Hand-painted via a projection process, like paintings of 1961–62 such as Before and After, Wigs, and Dr. Scholl’s Corns, the canvas is left partly unfinished, and Warhol employs a light touch with an abstract brushstroke. On this canvas the figure of Christ recurs four times, while hands appear repeatedly. Thomas’s finger pointing to the sky, intimating that heaven knows he is free of guilt, appears prominently next to the “eye” in the Wise potato-chip logo.33

Pulled from a New York Post headline, the phrase “The Big C” appears under Christ’s face in the lower-left center of the canvas. For Dillenberger the phrase references Warhol’s fear of cancer, but this account tells only half the story. The source material for the painting, in the archives of The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, is a collage made up of headlines from the New York Post, motorcycle ads, and clippings reading “the Big C” and “AIDS” cut from a front-page article in the Post (fig. G). Warhol ultimately left out the AIDS headline while keeping the more covert “The Big C,” but given the direct references to “gay cancer” in his diaries, it becomes clear that this image of Christ was connected for him to the rapid rate at which people were dying around him. “The Big C” was synonymous with AIDS. The Last Supper (The Big C) reflects on sex and shame through appropriated images of Christ’s betrayal, the piercing owl’s eye (the Wise logo), and the numbers 699, appropriated from a price tag—$6.99—but indexing both the sexual position “69” and the “mark of the beast,” 666, in the Book of Revelations. Even the details of Christ’s feet at the far right of the canvas seem to point to the notion of punishment: for Steinberg, writing on Leonardo’s Last Supper, “as [Christ’s feet] rejoin the rest of the body, they foreshadow it glorified; and they foreshadow it crucified.”34 The image of Christ offering his flesh in the Eucharist was a symbol of salvation during a time of suffering, an unusually personal and emotional image for Warhol. In keeping with the complexities of his construction of death in the Death and Disasters, and with its repression in the diaries, the painting speaks of sex and of judgment. It is an allegorical triangulation of mourning, punishment, and fear.

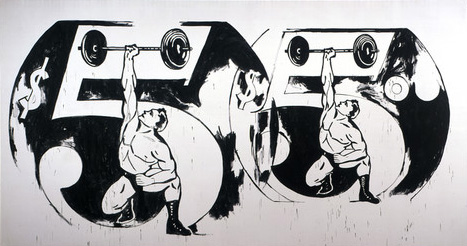

Warhol’s one canvas referencing AIDS directly, AIDS, Jeep, Bicycle, is misrepresented by Flatley’s description of it as the artist’s only response to the crisis.35 Seen apart from the Last Supper works, this painting may feel like an anomaly, with its unusual juxtaposition of seemingly disparate objects. It is a large canvas, nearly nine feet across, and its broad sweeping brushstrokes, drips and droplets, unfinished look, and mix of advertising images and newspaper headlines—one of them an oversize headline about AIDS—mirror the style of contempo-raneous paintings such as The Last Supper (The Big C) and the large Double $5/Weightlifter (fig. H). The source material for AIDS, Jeep, Bicycle, in the archives of The Andy Warhol Museum, unlocks the connection between it and the Last Supper series. A collage of taped-together source material for The Last Supper (The Big C) includes the same New York Post headline used in that painting, so that the two works function as sister canvases. Warhol’s allegorical response to the epidemic becomes more obvious when these two works are considered in concert.

Warhol—Il Cenacolo, the first exhibition of the Last Supper series, in Milan in 1987, came at a moment when the disease was manifesting powerfully within Warhol’s direct circle. Iolas, the gallerist who gave him both his first exhibition, in New York in 1952, and as it turned out his last, Warhol—Il Cenacolo, died of AIDS just five months after the opening of the Milan show. When the show opened, in January of 1987, Iolas was in the advanced stages of illness and was relegated to a sanatorium. Warhol surely felt that the disease was surrounding him. Death, which Warhol had portrayed through saintlike beauty in 1947 White and surreal crucifixion in White Burning Car (1963), is embodied in the depiction of Christ in the Last Supper paintings as a personal meditation on shame and salvation.

Discussing Warhol’s work in Pop Out, Flatley explores the complex workings of identification, what he calls the “poetics of publicity,” and the “intimate relation” between portraiture and mourning through a process of negation and embodiment, between “being public and being a body.” As he states, Warhol understood that “to become public or feel public was in many ways to acquire the sort of distance from oneself that comes with imagining oneself dead.”36 This argument holds true for much of the artist’s work—the Marilyn Monroe paintings, for example, which hollow out their references to the star while memorializing her death. There is an oversight in Flatley’s scholarship, though: his dismissal of Warhol’s handling of the AIDS epidemic. He claims that Warhol’s “failure to address AIDS surely stemmed in part from his phobic and shame-filled relation to illness.”37 It is true that Warhol had a lifelong, conflicted concern with illness and health, expressed in his diaries and in autobiographical books such as POPism (1980). But his shame was rooted in the physical expression of illness, and in the daily trauma involved in trying to hide his blotchy, two-toned complexion and the severe scarring from the surgeries resulting from his shooting. His response to AIDS was intimately connected to both his religious faith and his concealment of his sexuality. In fact Warhol’s response fits well with Flatley’s overarching argument about Warhol’s insights into the public consumption of images. In the face of a spectacle devoid of compassionate or positive images of people living with AIDS, Warhol’s response wasn’t a failure but a confession of love and fear and an expression of mourning. He gave AIDS a face—the mournful face of Christ.

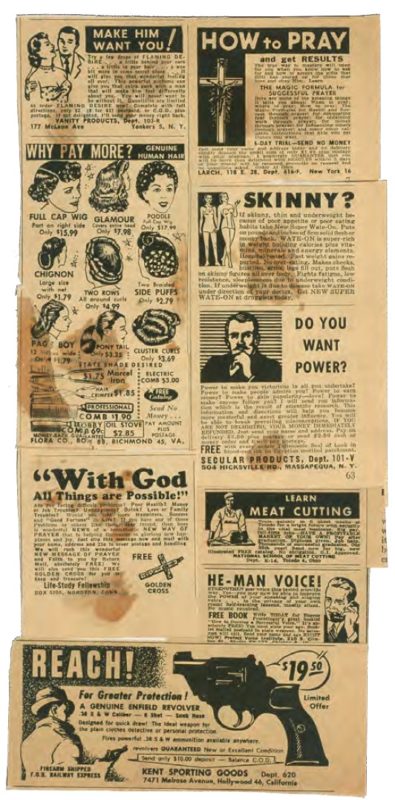

The source collage for The Last Supper (The Big C) and AIDS, Jeep, Bicycle, a hybrid of advertisements, bears a significant resemblance to some of Warhol’s earliest source material from 1961. That year, for his first Pop paintings, he cut headlines and advertisements from such tabloids as the National Enquirer and assembled the clippings into two collages, tabular images of sexual and spiritual desire. The ads—“Make Him Want You,” “How to Pray,” “Skinny?” “Do You Want Power,” “With God,” “Learn Meat Cutting,” “He-Man Voice!” and “REACH! for Greater Protection”—read like a list of repressed wish-fulfillments for Warhol, who in 1961 was undergoing a physical and professional transformation (fig. I).38 In 1957 he had sought plastic surgery to reshape his nose, had started wearing wigs to cover his hair loss, and had discarded his “Raggedy Andy” suits for a trendier look of sunglasses, narrow ties, and tighter suits, all in the pursuit of assimilating into the hypermasculine and exclusive circles of the New York art world. His first canvases—works such as Before and After (1961–62; pages 188–89), Wigs (1961; page 186), and Strong Arms and Broad Shoulders, created before the now-famous Campbell’s Soup Cans paintings of 1962—focused on beauty, pain, transformation, and assimilation. The pairing of coded sexual language, in phrases such as “Make Him Want You” and “Learn Meat Cutting,” with instructional advertisements for prayer and divine power is echoed in Warhol’s choices of black-and-white advertisements over twenty years later, in 1985–86, when he was working on the Last Supper series. Such paintings as Heaven and Hell Are Just One Breath Away! (1985–86; page 349), The Mark of the Beast (1985–86; page 349), and Repent and Sin No More! (1985–86; page 348) bring faith and sexuality together again, this time at a moment of intense public scrutiny of homosexuality during the moral crisis of the AIDS epidemic.

The crisis during the early stages of the epidemic was not simply one of images but one of language. As Paula A. Treichler has argued, the confusion emerged from a deep symbolic constriction of how we think and speak about disease.39 The scientific and medical communities were subject to the same metaphors and biases as the general population. As Treichler writes, “There is a continuum, then, not a dichotomy, between popular and biomedical discourses . . . ‘a continuum between controversies in daily life and those occurring in the laboratory,’ and these play out in language.”40 The ambiguity of the medical community’s language on the transmission and prevention of AIDS contributed to a rapid outbreak of fear and rumor in the general public. At the same time, the media and the medical community employed an overabundance of judgmental, moralistic, and religious language in their discussion of AIDS. In the early stages of the outbreak, for instance, cases in New York hospitals were referred to as “WOGS: the Wrath of God Syndrome.”41 More important, the contracting of AIDS was understood as the result of deviant behavior, whether through multiple sex partners, drug use, or prostitution. Given the manner in which this shame-based rhetoric took root in the public consciousness, Warhol’s juxtapositions of Christ with references to “gay cancer” and AIDS become a clear response to the crisis.

Once we situate Warhol’s late works within the AIDS epidemic, his series of black-and-white advertisement paintings take on a prescient tone in relation to the culture of fear that the crisis was creating. Private sexual lifestyles were becoming the subject of public scrutiny. The Mark of the Beast, Repent and Sin No More!, and other works from this series point to the moralistic assault directed at gay men by the media, which often positioned them as deviant and deserving of the full punishment of this silent killer. The image of a hand branded with the number 666 points not only to the sarcoma that often accompanied the virus but also to the violence of the period’s public discourse, which had produced the threat of branding or tattooing HIV-positive homosexuals.42 This violence permeated Warhol’s personal and professional world.

In March 1987, just a month after Warhol’s death, Larry Kramer founded the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP). A year later, Douglas Crimp published “AIDS: Cultural Analysis, Cultural Activism,” a special issue of the journal October, while artist collectives like Gran Fury fought to reposition the spectacle of AIDS from associations of isolation and shame to assertions of strength and community. Warhol’s hand-painted religious works, created just before this period of activism and resistance, went unshown during his lifetime and were crafted in his studio without the direction of a commission or a gallery show. The scholarly discourse that has positioned his work as a “failure” in the face of the AIDS crisis results in part from insufficient research and more still from a dismissal of the complexities of the artist’s lived experience as both a homosexual and a Byzantine Catholic, and of the deep conflicts visible in his work between illness and physical perfection.

In this broader view, it seems fitting that Warhol’s interpretation of the AIDS crisis would find its most complete expression in depictions of Christ and the Last Supper. More than a demonstration of reverence for Leonardo’s masterwork, or even an unveiling of his own Catholic faith, Warhol’s Last Supper paintings are a confession of the conflict he felt between his faith and his sexuality, and ultimately a plea for salvation from the suffering to which the homosexual community was subjected during these years. AIDS had generated a new way to brand the bodies of homosexual men as frightening symbols of moral decay and targets for punishment. From this perspective, these paintings can be understood as some of the most personal and revealing works of Warhol’s career. His response to the crisis, a deeply personal one, was in plain view, right on the surface of his canvases.

Acknowledgements

Reprinted from Andy Warhol—From A to B and Back Again, by Donna De Salvo, published by the Whitney Museum of American Art and distributed by Yale University Press. © 2018 Whitney Museum of American Art.

Endnotes

- See, respectively, Jennifer Doyle, Jonathan Flatley, and Josè Esteban Muñoz, eds., Pop Out: Queer Warhol (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1996); Douglas Crimp, Our Kind of Movie: The Films of Andy Warhol (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2012) and Callie Angell, Andy Warhol Screen Tests: The Films of Andy Warhol Catalogue Raisonné (New York: Harry N. Abrams and the Whitney Museum of American Art, 2006); and Andy Warhol Photography, exh. cat, Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, and Hamburg Kunsthalle (Zurich: Stemmle, 1999). ↵

- See Crimp, “Getting the Warhol We Deserve,” Social Text, no. 59 (Summer 1999): 49–56. See also Robert Rosenblum, “Warhol as Art History,” in Kynaston McShine, Andy Warhol: A Retrospective, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1989), pp. 25–37. ↵

- There are discrepancies in the record on the number of works in the exhibition: the catalogue lists twenty, but Corinna Thierolf cites a conversation with a conservator to suggest that there were twenty-two. See her “All the Catholic Things,” in Carla Schulz-Hoffmann, ed., Andy Warhol: The Last Supper (Ostfildern-Ruit, Germany: Cantz, 1998), p. 48, n. 13. ↵

- See ibid., p. 23. ↵

- Jane Daggett Dillenberger cites this number, which would surely include works on paper, sculpture, and paintings. See Dillenberger, “Preface,” in The Religious Art of Andy Warhol (New York: Continuum, 1998), p. 10. ↵

- See Sarah Boxer, “The Many Veils of Meaning Left by Leonardo,” New York Times, July 14, 2001, available online at www.nytimes.com/2001/07/14/books/the-many-veils-of-meaning-left-by-leonardo.html (accessed November 26, 2017). ↵

- See Leo Steinberg, Leonardo’s Incessant “Last Supper” (New York: Zone Books), 2001. ↵

- See Boxer, “The Many Veils of Meaning Left by Leonardo.” ↵

- See Thierolf, All the Catholic Things, pp. 23–24. ↵

- See Steinberg, “The Subject,” in Leonardo’s Incessant “Last Supper,” p. 36. ↵

- See John Denison Champlin, ed., Cyclopedia of Painters and Paintings, 3:32 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1887). Available online at https://archive.org/stream/cyclopediaofpain005381mbp#page/n11/mode/2up (accessed March 5, 2018). ↵

- See Ben Cosgrove, “‘The Most Beautiful Suicide’: A Violent Death, an Immortal Photo,” Time, March 19, 2014, available online at https://time.com/3456028/the-most-beautiful-suicide-a-violent-death-an-immortal-photo/ (accessed November 26, 2017). ↵

- Simon Watney, “The Spectacle of AIDS,” in Douglas Crimp, ed., AIDS: Cultural Analysis, Cultural Activism (Cambridge, MA.: The MIT Press, 1998), p. 78. ↵

- Dillenberger, The Religious Art of Andy Warhol. Dillenberger refers to AIDS just once, and this in relation to Warhol’s Skulls of the early 1970s. She states, “The resurgence of skull imagery accompanied punk culture and is related to anxiety over the spread of AIDS as well as the escalating threats of nuclear war and ecological disasters.” The connection is odd, since AIDS did not surface in public consciousness until the early 1980s. Ibid., p. 71. ↵

- Flatley, “Warhol Gives Good Face: Publicity and the Politics of Prosopopoeia,” in Pop Out: Queer Warhol, pp. 119–23. ↵

- Lawrence K. Altman, “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals,” New York Times, July 3, 1981, available online at www.nytimes.com/1981/07/03/us/rare- cancer-seen-in-41-homosexuals.html (accessed November 27, 2017). ↵

- Altman, “New Homosexual Disorder Worries Health Officials,” New York Times, May 11, 1982, available online at www.nytimes.com/1982/05/11/science/new- homosexual-disorder-worries-health-officials.html (accessed November 27, 2017). ↵

- “Saturday, February 6, 1982,” in The Andy Warhol Diaries, ed. Pat Hackett (New York: Warner Books, 1989), p. 429. ↵

- “Tuesday, May 11, 1982,” in ibid., p. 442. ↵

- Ibid., pp. 429, 432, 442, 460, 461, 469, 472, 739. ↵

- Bob Colacello, Holy Terror: Andy Warhol Close Up (New York: Random House, 1990), p. 585. ↵

- “Friday, June 12, 1981,” in The Andy Warhol Diaries, p. 387. ↵

- Amy DiPasquale, archivist, Cantor Arts Center, Stanford University, tele-phone conversation with the author, November 2017. ↵

- “Thursday, April 30, 1981,” in The Andy Warhol Diaries, p. 377. ↵

- “Monday, May 25, 1981—East Falmouth—New York,” in ibid., p. 383. ↵

- Warhol mixed his personal relationships with work from his very beginnings in New York, when his career as a commercial artist involved help from his mother, Julia Warhola, and one of his earliest boyfriends, Ed Wallowitch, a photographer who was involved with him in the late 1950s. Warhol used Wallowitch’s photo-graphs as source material for his early Campbell’s Soup paintings. See George Frei and Neil Printz, eds., The Andy Warhol Catalogue Raisonné, vol. 1, Paintings and Sculpture 1961–1963 (New York: Phaidon, 2002), pp. 95–96. ↵

- On the public and medical confusion around the spread of AIDS, and the public perception of casual contamination, see Paula A. Treichler, “AIDS, Homophobia, and Biomedical Discourse: An Epidemic of Signification,” in Crimp, AIDS: Cultural Analysis, Cultural Activism, pp. 31–70. Many people in Warhol’s circle, including Bob Colacello, Christopher Makos, and Halston, expressed doubts that the relationship between Warhol and Gould was sexual. Colacello for example writes, “Jon Gould told Katy Dobbs that his relationship with Andy was ‘asexual,’ explaining that ‘the shooting had affected Andy’s sex life, because he was embarrassed by his body, with all the scars, and was uncomfortable a lot and in pain.’ Halston said he thought that the most that ever happened in Montauk ‘was while Jon was taking a shower, Andy probably looked at him and got, you know, some satisfaction.’” Colacello, Holy Terror, p. 626. The details of Warhol’s sexual life and relationships are often neglected throughout the discourse, from early boyfriends such as Wallowitch and Alfred Carlton Willers to the young Danny Williams. With Gould, the doubt seemed to stem mostly from a general sense of fear and jealousy among members of Warhol’s circle, who worried that the artist would be taken advantage of by a younger man. Colacello, Makos, and Vincent Fremont all expressed resentment over the attention that Warhol gave to Gould, whether by including him in business meetings or by showering him with gifts, party invitations, and even works of art. Even if we entertain the unfortunate myth that Warhol’s sex life was asexual and voyeuristic, which is hard to believe given his and Gould’s living arrangements, it is irrelevant because the public rhetoric of AIDS at this moment was so potent and confusing. In any case, I find the narrative of Warhol’s asexuality unproductive in exploring the full spectrum of his private and professional life. ↵

- “Saturday, February 4, 1984,” in The Andy Warhol Diaries, p. 552. ↵

- Hal Foster, “Return of the Real,” in Foster, Return of the Real (Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 2001), p. 132. ↵

- Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1981), p. 26. ↵

- “Sunday, September 21, 1986,” in The Andy Warhol Diaries, p. 760. ↵

- See Colacello, Holy Terror, p. 642. ↵

- See Steinberg, “The Hands and Feet,” in Leonardo’s Incessant “Last Supper,” p. 69. ↵

- Ibid., p. 63. ↵

- See Flatley, “Warhol Gives Good Face,” p. 122. ↵

- Ibid., p. 105. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- See Gavin Butt, “Dishing on the Swish, or, the ‘Inning’ of Andy Warhol,” in Between You and Me: Queer Disclosure in the New York Art World, 1948–1963 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005), pp. 106–35, and Jessica Beck, “Beauty Problems,” in Andy Warhol: My Perfect Body, exh. cat. (Pittsburgh: Andy Warhol Museum, 2016), pp. 9–18. ↵

- See Treichler, “AIDS, Homophobia, and Biomedical Discourse,” p. 31. ↵

- Ibid., p. 35. ↵

- Ibid., p. 52. See also David B. Morris, Illness and Culture in the Postmodern Age (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), p. 190. ↵

- Discussing the homophobic rhetoric accompanying the spread of the AIDS epidemic, Watney cites a New York Times op-ed in which William F. Buckley argues that homosexuals should be tattooed with their test results: “everyone detected with AIDS should be tattooed in the upper forearm, to protect common-needle users, and on the buttocks, to prevent the victimization of other homosexuals.” Buckley, “Crucial Steps in Combating the Aids Epidemic; Identify All the Carriers,” New York Times, March 18, 1986. See Watney, “Moral Panics,” in Watney, Policing Desire: Pornography, AIDS, and the Media, Media and Society series, ed. Richard Bolton (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), p. 44. ↵