Book ExcerptLessons Learned in Pittsburgh

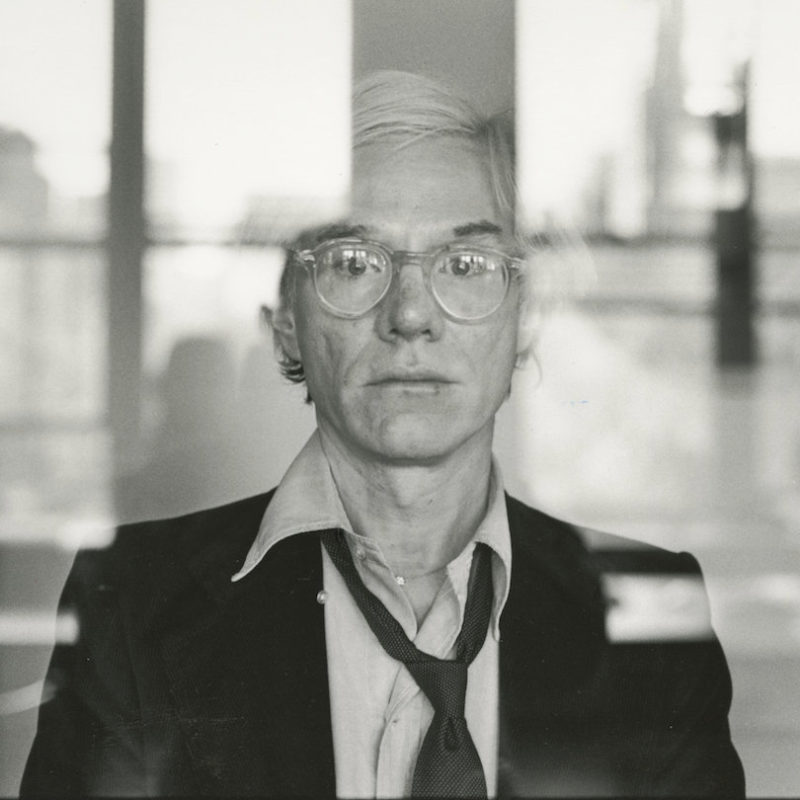

Duane Michals, Andy Warhol (c. 1974). Courtesy Duane Michals and DC Moore Gallery, New York, © 2018 Duane Michals.

Crossing the Carnegie’s soaring atrium on the way to the new art classes this school kid had signed up for—there are photos of pupils making that trip—Warhol was treated to a deluxe suite of murals that began with a hellish view of the city’s mills, depicted from precisely the smoke-choked hills of Soho where Warhol was born. As he and his classmates climbed the stairs, the smoke was shown giving way before the Angels of Art anointing an ascendant figure of Labor—Andrew Carnegie himself, costumed as a knight. This was an allegory of cultural and social ascension that Warhol seems to have taken to heart.

The kids in the museum’s art classes were known as Tam o’Shanters, apparently a Scottified, Carnegie’d reference to the classic Montmartre artist’s beret. The world-famous program was just a few years old when Warhol joined. The most notable of the program’s teachers was a certain Joseph Fitzpatrick, who happened to be a Warhola neighbor in tidy South Oakland. A slim, tall man who taught in a natty suit and tie, he was barely in his thirties when Warhol knew him. He’d spent a few years as art supervisor for the public school system, which had a notably ambitious cultural agenda for its students, and then taught at Warhol’s own Schenley High in Oakland. Fitzpatrick was famously strict, and his lessons might seem a touch Victorian: as many as six hundred children sitting in the Institute’s grand Music Hall—“ the largest art class in the world”—all in ties and tidy dresses and all drawing pictures of the same thing. But Fitzpatrick also voiced more modern attitudes: “I looked for the boys and girls to express themselves in their own ways. In other words, I didn’t say that a drawing had to be this way, or that way . . . but I did say it had to be excellent.”

Another Carnegie teacher wanted his students “to learn to see beautifully.” He played Debussy on the piano while the little Tam o’Shanters drew “forms that sprang into life from hearing the inspiring notes.” Sometimes that teacher made his own abstractions as the little ones sang.

Fitzpatrick and his colleagues had their charges “all on fire . . . about art, as an idea” according to one Tam o’Shanter friend of Warhol’s. Warhol prospered, winning accolade after accolade for “very realistic work . . . with a decorative quality that was very becoming,” recalled Fitzpatrick, more than a half century after Warhol was supposed to have made that impression. “I distinctly remember how individual his style was. . . . From the very start he was quite original.” Yet in 1939, the Carnegie art classes had almost twenty-five thousand names on their attendance sheets, with several kids nominated from every public and private school, so it would be a mistake to dwell too much on young Warhol as part of some budding artistic elite. Even his brother John had enough artistic talent to start classes there at the same time as Warhol, but quit because he didn’t have his sibling’s willingness to miss out on playing ball with the neighborhood boys. A statement by the Carnegie might as well have had Warhol in mind: “We are looking forward to a time when we shall search out and find the potential artist. We shall nurture him, like the queen bee, on special artistic food. . . . [s]o that a leader in this field shall not be lost.”

If the lessons were important for Warhol’s future, their setting may have mattered even more. The Carnegie art students sketched and eventually made watercolors right inside the museum’s Old World galleries, where Warhol got the chance to know the museum’s permanent collection. In those early days, there weren’t many masterpieces on view—Andrew Carnegie had wanted his museum to focus on recent art of a conservative bent—but its decent holdings in Old Master portraits set Warhol up for his career as the greatest portraitist of his era.

The shortcomings in the Carnegie’s permanent collection were made up for by an ambitious roster of special exhibitions, which would have fleshed out the thorough grounding in art history Warhol had got from Miss Vickermann at his elementary school. Looking at the exhibition program from Warhol’s time as a student at the Carnegie museum is like looking at a prehistory of his career. When he was almost twelve, the museum brought in a show of European “masterpieces,” which gave Warhol his first taste of classic works by the likes of Rembrandt, Rubens and Poussin, setting the bar high for his later ambitions.

In 1941 there was a blockbuster Picasso show, on tour from the Museum of Modern Art, which included Guernica, the era’s celebrity painting. It let the young Warhol take the measure of his most important twentieth-century rival, who was a special favorite of his in college. Later, at the height of his Pop Art fame, Warhol made the rivalry explicit by wearing the striped T-shirts Picasso was famous for.

A silkscreen exhibition gave him early exposure to his signature Pop medium. Surveys of the French outsider Henri Rousseau and of American “primitives” sparked his lifelong interest in outsider and folk art, which was a vital model for his work in the 1950s and which he collected all his life. As late as 1976, Warhol was still including “American primitive painters” on his list of all-time favorite artists. When a Pittsburgh paper raved about the Carnegie’s “magnificent” survey of Rousseau, it described him as an artist who “paints a child’s world in adult terms. . . . We suspect many modern artists of also going back to their childhood, only their excursions lack the unforced directness [of] Rousseau.” A good part of the appeal of Warhol’s 1950s illustrations came from their simulation, at least, of a childlike directness.

A Carnegie survey of contemporary self-portraits launched Warhol into depicting himself, which he started early and never abandoned. Other Carnegie exhibitions—The Artist as Reporter, The American Weekly Exhibit of Magazine Art, annual photo shows, a landmark survey of Russian icons—seem tailor-made to turn Warhol into the particular artist he became. In April 1940, the Carnegie published a photo of a crowd of its art students. One of them is a scrawny young man whose shock of blond hair bears a suspicious resemblance to the hairstyle of a certain preteen named Andrew Warhola. Whether that’s him in the shot or not, what really matters is what those Saturday pupils are doing: They are hard at work sketching the piles of advanced contemporary art that the museum brought in once a year for its famous Carnegie International.

Every October since 1896 the museum had hosted that show, the country’s only survey of the latest in world art, rivaled only by the Venice Biennale in scale and importance. During Warhol’s early Pittsburgh years, it was organized by a man named Homer Saint-Gaudens, son of the celebrated sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens. Homer was brought up among America’s first modern artists—John Singer Sargent painted him at age ten—but he was also a toff who captained the Harvard fencing team. In Paris or New York, his tastes might have seemed a bit tame, but he claimed his Internationals had been wild enough to blow up Pittsburgh’s “self-contented ignorance.” The local press agreed with him, and didn’t like it. One paper gave front-page play to a New York critic’s reactionary attack on the first prize that the International’s “stupid” jury awarded to a quite demure Picasso portrait.

Of course, controversy had its benefits (another important lesson for Warhol): Crowds thronged to one International that included a controversial first-prize painting titled Suicide in Costume. Its artist said that his grotesque dead clown symbolized “our civilization.” The painting was the talk of Pittsburgh for decades. But by 1950, a year after Warhol left the city, Saint-Gaudens could claim that he’d won the fight for Pittsburghers’ hearts: “They used to spit at 50 yards at a modern painting; now they say, ‘I don’t know anything about it—it may be all right.’ ”

On top of teaching Warhol that backing the avant-garde paid cultural and social dividends, the Carnegie International under Saint-Gaudens promoted an advanced view of art as involved in the world around it. It regularly showcased works about the horrors of industry and Jim Crow, sometimes even including black artists in its mix. Art, wrote Saint-Gaudens, “must justify itself; must be measured by its effects on the social orders.” Warhol took that lesson to heart. His mature work certainly did have—was intended to have—such an effect, at a time when many other artists were busy exploring and expressing their interior lives. The first-prize picture at the Carnegie’s 1941 exhibition depicted lynchings and other troubles of the American South; it might as well have been one of Warhol’s highly charged Death and Disaster pictures, in embryo, with their depictions of police attacking black marchers and electric chairs awaiting their next victims.

In 1940, with war raging in Europe, the annual show got cut back to artists in the U.S.A., including émigré art stars such as Max Ernst and George Grosz and major American figures such as Georgia O’Keeffe, Milton Avery, and Edward Hopper. It’s especially nice to know that the young Warhol had a chance almost every year to see some notable painting by Stuart Davis, the one true avatar of Pop Art in this earlier generation. Davis’s pictures of store signs and cigarette packs, done in the bold, bright styles of package design, set an example for Warhol of how it was possible to make world-class pictures that riffed on popular culture. Davis’s influence was acknowledged decades later by Henry Geldzahler, the powerful curator who “discovered” Warhol and Pop Art.

As a Pittsburgh teenager Warhol had no way of knowing that by scanting abstraction, the Carnegie’s annual was missing out on the sharpest cutting edge. The Warholas shared Pittsburgh’s general skepticism about abstract art, and that may have been at the root of Warhol’s later tendency to see abstraction as a desirably daring form he didn’t quite have access to.

“American art, now in the process of creation, belongs to the future . . . a fresh, vigorous creation of a new form rapidly approaching maturity, perhaps its Golden Age,” proclaimed Warhol’s college art text, written while Warhol was still in elementary school. That important—but in fact incorrect—idea that American English was the normal language of the avant-garde would already have been planted in the young Warhol by the Carnegie’s wartime annuals. In the 1930s, when those lines in the textbook were written, they represented wishful thinking, but their ideas still set a target for Warhol’s ambitions. A truly American creativity, his textbook informed him, would someday “transcend the incomplete experiments of the early twentieth century so that a universal art and a more comprehensive meaning may be created for mankind’s future.” Warhol gave himself a role in building such a future.

Excerpted from Warhol, published by Ecco.