EssayHow Warhol’s Complicated Relationship with Catholicism Influenced his Art

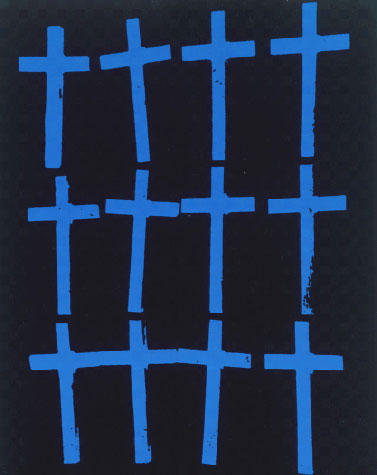

Andy Warhol, Crosses (Twelve) , 1981–82

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

1998.1.264

“They do not see you as you want to be….They see you as you are. You are the light.”

In the summer of 1967, thousands of miles away from the Vietnam War, American countercultural movements bloomed during the “Summer of Love.” Hippies flocked to the Haight-Ashbury district in San Francisco and to New York’s East Village, centers where social change and creativity were celebrated. Similarly, artists, poets, musicians, and other creators arrived at Warhol’s Silver Factory, a nexus of experimentation, socializing, and cultural collaborations. Fueled by the success of The Chelsea Girls, which premiered in September 1966, Warhol continued filming the chaotic underground scene, complete with sex, drugs, and rock and roll. While Warhol’s work at this time was seemingly antithetical to “religious” practices, metaphors of the Catholic faith are very much present in the undercurrents of his artistic production. I propose that Warhol’s genuine faith was shown through his art that summer. This faith inspired Warhol to evoke the immanence of God through his art, specifically in a series of five unfinished reels of film depicting sunsets. While many of these reels capture a spiritual, transient experience, my focus will be on one particular sunset that includes a soundtrack by Warhol Superstar Nico originally labeled as reel 77 and incorporated into Warhol’s twenty-five-hour film screening **** (Four Stars) in December 1967 (fig. 1).

The connection between Warhol’s religion and his artistic production was not deeply explored until after he died in 1987. While his Byzantine Catholic background and religious practices had been previously acknowledged by friends, family, and employees, it was not often publicized to the media. One exception was an Esquire magazine article from 1966, in which Warhol’s pious mother, Julia, boasted to the reporter, “He [is a] good religious boy.”1 Published after his death, The Andy Warhol Diaries reported the artist’s daily activities for decades, with more than fifty mentions of his going to church.2 In Bob Colacello’s memoir Holy Terror, the former insider described the artist doing “all the Catholic things . . . taking holy water, genuflecting, kneeling, praying, and making the Sign of the Cross” when they visited the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico City.3 In that moment Colacello realized Warhol’s devotion was not an act but a fundamental part of his life.4

Warhol made little effort to elaborate on his religious beliefs or Christian themes in his art. However, some of Warhol’s first experiences of visual culture were cultivated in the pews of St. John Chrysostom Byzantine Catholic Church in the Ruska Dolina neighborhood of Pittsburgh (fig. 2). At the center of this church stands a massive iconostasis, or icon screen, adorned with gilded images of Christ and the saints, which many scholars claim inspired Warhol’s iconic portraits and seriality.5 The Byzantine Catholic faith, part of the Eastern lung of Christendom, is distinctive for its symbolic interpretations, rituals, and visual richness that engage all the senses: sight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch.6 Although Warhol began attending Roman Catholic Mass once he moved to New York, his experiences in the Byzantine Catholic Church would have undoubtedly remained influential.

After the 1966 exodus of Edie Sedgwick, the “rare representative of the WASP aristocracy,” lapsed Catholics composed the vast majority of the Silver Factory regulars.7 Warhol’s nonconformity with regard to Catholicism made him fit perfectly into this cohort. Photographer and Warhol collaborator Christopher Makos reflected on the relationships: “A lot of his friends were Catholic. . . . He may have related better to us Catholics because we all had the same background: Mass, priests, nuns, Catholic school, a sense of guilt.”8 Among this ex-Catholic counterculture were the renamed and ordained Superstars: Gerard Malanga, Brigid “Polk” Berlin, Ultra Violet, (Pope) Ondine, Ingrid Superstar, Viva, Joe Dallesandro—even Valerie Solanas, the woman who tried to take Warhol’s life.9 Critic Robert Hughes caustically observed that “the Factory resembled a sect, a parody of Catholicism enacted (not accidentally) by people who were or had been Catholic, from Warhol and Gerard Malanga on down.”10

Whether by design or sheer serendipity, the growth of Warhol’s lapsed-Catholic entourage in the summer of 1967 coincided with the production of film reels that held religious themes, all of which would eventually be incorporated in various capacities into **** (Four Stars). One of these was the film Imitation of Christ, a seemingly improvised narrative that portrayed the former child star Patrick Tilden-Close as a Christlike figure among a highly dysfunctional household, including the scene-stealing Nico reading aloud from Thomas à Kempis’s De Imitatione Christi. In contrast to Warhol’s fixation on actors’ bodies in Imitation of Christ, the other film reels, depicting sunsets, lacked a carnal focus. This material is considered to be part of Warhol’s incomplete “sunset” project intended for the 1968 world’s fair in San Antonio. The most evocative of them, reel 77, features one static thirty-three minute shot of the sun setting over the Pacific Ocean.

Unknown to many, the sunset project was originally commissioned by renowned art collectors John and Dominique de Menil—a Catholic power couple based in Houston—and sponsored financially by the Catholic Church.11 In the early summer of 1967 John de Menil asked Warhol to create a work that would be featured in a Vatican-sponsored “ecumenical pavilion”—a “church where various denominations could be in communion”—at the upcoming HemisFair ’68.12 Due to the ambiguities surrounding its creation, the project has been largely overlooked when considering the Warhol canon. Yet it should be taken seriously as both a salient piece of Warhol’s oeuvre and a deep, metaphorical religious work. Not only are the sunset reels connected to the sole commission Warhol received from the Catholic Church, they are also the first works he created with intentional spiritual content since the launching of his Pop aesthetic in 1961.

HemisFair ’68

The story of the Sunset commission begins with the organizers of the 1968 world’s fair, which was to be held in San Antonio (fig. 3). HemisFair ’68 joined a rich tradition of international expositions that “brought together cultures and ways of life, styles and ideas, fragrances and aromas from all the corners of the globe.”13 At each international exposition, countries, states, religious entities, and other organizations could exhibit the highlights of and advances made by their cultures. The Vatican had a strong presence in the expos of the 1960s, maintaining the second most visited pavilion at the 1964 world’s fair in New York, where Michelangelo’s Pietà was displayed.14 This masterpiece drew so much attention that even Warhol commented on the ostentatious pomp surrounding it, observing that the Pietà appeared within a “Pop context.”15 The Vatican was also present at Montreal’s Expo 67 in an ecumenically themed Christian Pavilion, which Warhol may have visited with John and Dominique de Menil, Fred Hughes, and architect Howard Barnstone (fig. 4). Lacking overt religious content, the pavilion included a photo exhibit about contemporary life and a section called “The Dark Side of Man,” comprising a cinema screening 16mm film clips of human atrocities such as nuclear explosions and concentration camps.16 Through these involvements, the Catholic Church was able to reach secular audiences in ways that standard church activities could not.

Based on the success of these previous endeavors, HemisFair ’68 president Marshall T. Steves approached Robert E. Lucey, the archbishop of San Antonio, in April of 1967 to invite the Vatican to participate in the expo.17 Although the arch-bishop initially suspected commitment from the pope to be unlikely, the Holy See agreed to support a HemisFair pavilion in late May or early June 1967. Upon reaching this agreement, the Catholic bishops of Texas decided to employ the arts department of St. Thomas University, a Catholic institution in Houston, to curate the pavilion due to its reputation for putting on stunning exhibitions. As the head of the arts department, Dominique de Menil was asked to organize and commission works for the endeavor.18 Despite refusing two or three times, she agreed on the condition that she would have complete freedom and no committee to get in the way. However, as she was traveling in Europe, the task fell upon her husband, John, to secure the contemporary “spiritual” works for the pavilion. In the end the Menils offered commissions to Warhol, Robert Indiana, Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, and Robert Rauschenberg on behalf of the Catholic Church, with only Warhol and Indiana fully obliging their request.19 While Warhol planned his film, Indiana created Love Cross, a cruciform assemblage of painted canvases that expressed the artist’s fascination with the spiritual nature of love.20

Sunrise/Sunset

Fred Hughes, a young Catholic dandy who worked for the Menils during the spring and summer of 1967, ultimately coordinated negotiations and planning for the Warhol commission.21 Metropolitan Museum of Art curator Henry Geldzahler had brought Hughes to the Silver Factory earlier that year, and Hughes immediately felt a rapport with Warhol.22 Hughes organized a Menil fundraiser for the Merce Cunningham Dance Company at Philip Johnson’s Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut, on June 3, 1967, and he insisted that the Velvet Underground play at the event.23 This was the first time the Menils met Warhol after falling in love with his work and purchasing two of his Flowers paintings from the Leo Castelli Gallery in 1965.24 Following the success of the fundraiser, Hughes approached Warhol on behalf of John de Menil about a film for the HemisFair ’68 Vatican pavilion.25

After Hughes arranged the deal with Warhol, John de Menil sent a letter to the artist on June 26, 1967, explaining the context of the work and the stipulations set forth by Archbishop Lucey. The archbishop opposed presenting classical religious art, feeling it antiquated in the modern milieu. Menil wrote that “religious art today just doesn’t exist . . . yet art and religion actually speak the same language where a true artist is involved—regardless of his own religious position.”26 The pavilion itself was to be designed by the prominent Houston-based architect Howard Barnstone, who was then working on the Rothko Chapel in Houston.

Warhol enthusiastically accepted the offer to participate in the project and suggested a film about a “Sunrise/Sunset.”27 The Menils agreed to the subject matter, and Warhol began filming the setting sun across the United States: one reel from a beach in East Hampton, Long Island; two of New York City across Central Park; one from the San Francisco suburb of Sausalito; and one off the coast of California (known as reel 77). At one point, according to correspondence with the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, he intended to film a sunrise over Lake Michigan, although this never came to fruition.28 Recalling the experience in POPism, Warhol stated, “I filmed so many sunsets for that project, but I never got one that satisfied me.”29 Despite Warhol’s attraction to modern civilization, the reels he shot reveal a quest to capture the natural progression of the waning sun through deep observation. Warhol’s Abstract Expressionist contemporaries understood this essence as the sublime: a deeply emotional visual experience that brings the viewer to what Dominique de Menil called “the threshold of the divine.”30 Several memos from John de Menil to Frank Bredeweg, then treasurer and controller of St. Thomas University, document that the Catholic Church was trying to raise $20,000 to fund the film. The transactions were brokered by Menil—he even offered to loan the church money so it could pay Warhol promptly.31 Although Warhol received $15,000 for his work, the film was never truly completed, and the ecumenical pavilion for the HemisFair ’68 failed to materialize.32 It is possible that funding was never secured for the pavilion itself, and the Catholic Church, already possessing a large following in the region, had less incentive to create an ambitious display than it had in past international expos. Warhol also moved on from the project and used the remaining funds from the commission to film Lonesome Cowboys in early 1968.33

Reel 77

The sunset reels were first included as part of Warhol’s twenty-five-hour film **** (Four Stars), which was screened just once, on December 15 and 16, 1967, at Jonas Mekas’s Film-Makers’ Cinematheque in New York City. Using two projectors, Warhol superimposed two films onto one screen, intertwining the sunset footage with the content of other reels.34 34 As segments in **** (Four Stars), the sunset reels cannot be called complete, self-contained “films” like Empire or The Chelsea Girls. In fact, Warhol did not officially name the reels as individual works, and the title “Sunset” was derived by scholars from the labeling found on the box, can, or reel itself. Of the five reels that could be considered part of the San Antonio commission, reel 77 has received the most attention for its spiritual nature in conjunction with a soundtrack by Nico added after the film was shot.35 Indeed, Warhol’s addition of a soundtrack makes it the most deliberately constructed and “finished” of the sunset films and suggests it may have been intended for HemisFair ’68 had the pavilion materialized.36 Regardless of where reel 77 was finally shown, it is clear that the circumstances of the commission prompted Warhol to infuse genuine spiritual content into the work.

From Warhol’s unmoving camera lens, reel 77 captures the summer sun setting off the coast of California. The ephemeral experience, a phenomenon of beauty, is metaphorically linked to creation and life, both in sacred and secular terms. Yet sunsets are also symbolically tied to the transience of life and the certainty of death. Warhol understood the dichotomy between life and death, as he demonstrated so many times before through his silkscreen paintings. Here he subtly crafted something meditative around the fragilities of life.

Just as Warhol’s Pop icons (e.g., Marilyn, Jackie, Liz) are metaphors for beauty and tragedy, here the evening light is represented and elevated in spiritual terms, recalling the icons from his childhood Byzantine Catholic iconostasis. Those images were not mere representations of holy figures; they were consecrated art that facilitated connection between the believer and the divine. A sunset does not simply function as a beautiful occurrence in nature; it is also a reminder of creation and human existence. I would argue that Warhol, familiar with the creation story from his own upbringing, might have had the Book of Genesis in mind when considering the sunset project. Without the sun, life on earth would not exist; and without the light of the sun, darkness would have no meaning. “In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth. And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters. And God said, Let there be light: and there was light. And God saw the light, that it was good: and God divided the light from the darkness” (Genesis 1:1-4; KJV). Warhol’s art uses the interplay of contrasting light and shadows again and again. Through the first fifteen minutes of foot-age in reel 77, the sun slowly drops, and the dusk transforms from a rich tangerine to a deep purple. On two occasions an airplane can be seen flying across the sky, suggesting that Warhol was filming close to a major metropolitan airport.37 In the last fifteen minutes dark abstraction envelops the evening horizon. Callie Angell, an adjunct curator of the Andy Warhol Film Project at the Whitney Museum of American Art, was the first to seriously examine reel 77 in the late 1990s, and she was struck by the robust colors and lines in the footage, equating it on several occasions to a Rothko painting.38 Through the entire experience Nico can be heard reciting poetry, possibly sourced from her own “dream-notebook.”39 Her haunting voice limns a narrative of life and death, light and darkness, and the presence of the divine: “Infinity is alive. . . . Death wants to be here. . . . You are the light. . . . His hands hold life. . . . The night is white. . . . They do not see me. They do not see you.”

The Sunset Returns

It is not clear why the HemisFair pavilion and Warhol’s project for it were never completed. Had Howard Barnstone completed the spiritual pavilion, it might still stand in San Antonio and complement his nondenominational Rothko chapel in Houston. Reel 77 was first shown at Rice University in Houston in 2000, and it was screened daily in the 2016–17 exhibition Andy Warhol: Sunset at the Menil Collection.40

Other works suggest that Warhol’s fascination with sunsets was not limited to film. One of Warhol’s mechanical studies—found in one of his 610 Time Capsules assembled starting in 1974—was made from a double-spread tear sheet from the April 26, 1968, issue of Time magazine. Strips of thick paper frame a cropped, vertically oriented sunset from an AT&T ad (fig. 5). No completed artwork has been identified that corresponds to the framing and positioning of the sun in this study. Warhol also addressed sunsets in a 1972 commission from architect Philip Johnson. Made for guest rooms in the Marquette Hotel (1973) in Minneapolis, the series is notable for its quantity (632 uniquely colored screen prints, 472 of which went to the hotel) and delicate ombré effect. When Warhol saw the series at the hotel in 1975, he commented on how great they looked.41 Within Warhol’s oeuvre it is easy to identify works with explicitly religious themes: Crosses, Raphael Madonna-$6.99, and, of course, the Last Supper series. Yet it is difficult to decipher whether or not these works are genuine expressions of faith or references to kitsch and pop culture. The theme of sunsets that emerged in the summer of 1967 is seemingly out of the ordinary for Warhol. Given the context of the commission, it is clear that he intended his film to be spiritual, if only to satisfy his patrons. After spending his entire career catering to a secular audience, the Catholic Church gave Warhol the opportunity to create a serious sacred work by employing the fundamental Catholic principles he had cultivated his whole life.

It is no surprise that the “sunset” commission fell into obscurity. Just like his clandestine religious practices, Warhol may have been too afraid of what the public might think if he appeared as a serious spiritual artist. As he admitted in a 1966 interview with Gretchen Berg, “I’m not the High Priest of Pop Art, that is, Popular art, I’m just one of the workers in it.”42

Endnotes

- Bernard Weinraub, “Andy Warhol’s Mother,” Esquire, November 1966, 101. ↵

- Andy Warhol, The Andy Warhol Diaries, ed. Pat Hackett (New York: Warner Books 1989). ↵

- Bob Colacello, Holy Terror: Andy Warhol Close Up (New York: HarperCollins, 1990), 160. ↵

- Colacello, Holy Terror, 160. ↵

- See Jane Daggett Dillenberger, The Religious Art of Andy Warhol (New York: Continuum, 1998), 17. ↵

- Bissera V. Pentcheva, “The Performative Icon,” Art Bulletin 88, no. 4 (2006): 631. ↵

- Colacello, Holy Terror, 93. ↵

- Christopher Makos, Warhol: A Personal Photographic Memoir (New York: New American Library, 1988), 53. ↵

- Other Catholics included Mario Montez, Jane Forth, Jack Smith, Geraldine Smith, Jackie Curtis, Candy Darling, Holly Woodlawn, Fred Hughes, and Paul Morrissey. ↵

- Victor Bockris, The Life and Death of Andy Warhol (New York: Bantam, 1989), 214. ↵

- John de Menil to Andy Warhol, June 26, 1967, Folder 13, “HemisFair ’68, San Antonio, Artists Commissioned by the de Menils, 1967,” Box 6, University of St. Thomas records, Menil Archives, The Menil Collection, Houston. ↵

- de Menil to Warhol, June 26, 1967. ↵

- Micol Forti, introduction to Revealing the Present through History: The Vatican and International Expositions, 1851–2015, by Rosalia Pagliarani, Micol Fort, and Federica Guth (Milan: 24 Ore Cultura, 2016), 10. ↵

- Warhol was represented at the 1964 New York World’s Fair by his installation Thirteen Most Wanted Men. It was separated from the Vatican pavilion by the Astral Fountain. ↵

- Andy Warhol and Pat Hackett, POPism: The Warhol ’60s (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1980), 135. ↵

- Rosalia Pagliarani, “The 1960s and the International Perspective of the Church,” in Pagliarani, Forti, and Guth, Revealing the Present, 173–77. ↵

- Dillenberger, Religious Art, 80. ↵

- Paul Taylor, “The Last Interview,” Flash Art (International Edition), no. 33 (April 1987): 41. ↵

- Warhol told an interviewer: “Since the Last Supper by Leonardo is the best painting in existence and since no one can buy it, Iolas asked me to make a copy so that anyone could take it home and put it in their living room.” Alexandra Farkas, “Incontro con Andy Warhol alla Vigilia del Suo Arrivo a Milano Dove Presenta una ‘Copia’ di Leonardo,” Corriere della Sera, n.d. quoted in Thierolf, “All the Catholic Things,” 50 (translation by the author). ↵

- Steinberg, Leonardo’s Incessant Last Supper, 53. ↵

- Warhol and Hackett, POPism, 217; J. de Menil to Warhol, June 26, 1967. ↵

- Rupert Smith quoted in Jörg Schellmann, ed., Andy Warhol: Art from Art (New York and Cologne: Edition Schellmann, 1994), 77. ↵

- Schellmann, Andy Warhol: Art from Art, 77. ↵

- Warhol, Diaries, 662. ↵

- Jean Baudrillard, The Consumer Society: Myths and Structures (London: Sage, 1998), 110. ↵

- Steinberg, Leonardo’s Incessant Last Supper, 17. ↵

- William Grimes, “The Man Who Rendered Jesus For the Age of Duplication,” New York Times, October 12, 1994. ↵

- A Sallman prayer card was found with a Byzantine Catholic calendar in one of Warhol’s Time Capsules. ↵

- Warhol and Hackett, POPism, 217. ↵

- Dominique de Menil, The Rothko Chapel: Writings on Art and the Threshold of the Divine (New Haven, CT; Houston: Rothko Chapel, 2010). ↵

- J. de Menil to Bredeweg, August 9, 1967. ↵

- Callie Angell, email to Vance Muse, February 9, 2000, Folder 13, “HemisFair ’68, San Antonio, Artists Commissioned by the de Menils, 1967,” Box 6, University of St. Thomas records, Menil Archives, The Menil Collection, Houston. ↵

- Angell, email to Muse, February 9, 2000. ↵

- David Bourdon, Warhol (New York: Abrams, 1989), 265 ↵

- Callie Angell to Dominique de Menil, November 7, 1997, “Andy Warhol-Artwork and Correspondence,” Box 19, Dominique de Menil 3363 San Felipe Collection Room Research files, Menil Archives, The Menil Collection, Houston. ↵

- Of the five “sunset” reels, three had sound; the soundtracks for two of the reels (reel 40 and reel 75) were recorded synchronously with the image when they were shot. Reel 77’s was the only soundtrack added in postproduction. ↵

- According to POPism, Warhol spent time in San Francisco filming Bike Boy and **** (Four Stars) during August 1967. ↵

- Callie Angell’s notes on “Sunset,” March 17, 2000, for screening at Rice University, Folder 13, “HemisFair ’68, San Antonio, Artists Commissioned by the de Menils, 1967,” Box 6, University of St. Thomas records, Menil Archives, The Menil Collection, Houston. ↵

- Richard Witts, Nico: The Life and Lies of an Icon (London: Ebury, 1993), 193. In Sausalito (a film segment apparently incorporated into **** [Four Stars]), Nico reads from her “dream-note-book,” saying, “A man is walking on the sea”—the same verse she used in the audio for reel 77. ↵

- Angell’s notes from March 17, 2000, (see note 38) state: “As far as I know, tonight is the first time ever that this Sunset film has been shown publicly on its own.” ↵

- Colacello, Holy Terror, 417. ↵

- Gretchen Berg, “Andy Warhol: My True Story,” East Village Other, November 1, 1966; reprinted in Kenneth Goldsmith, Reva Wolf, and Wayne Koestenbaum, I’ll Be Your Mirror: The Selected Andy Warhol Interviews: 1962–1987 (New York: Carroll & Graf, 2004), 90. ↵